The story of an intersection and two commercial anchors.

Building a neighborhood also means building community. The process builds intersections—places where friends meet, and strangers cross paths. By examining a place and its history, we can understand how it shaped lives through generations. The intersection of Farwell Ave and Irving Place is one I encounter regularly and acts as an anchor point in my life. I am not alone; in drawing from Knox and McCarthy, we can think of the lifeworlds of those past and present to whom this place is dear.

“Ways of being, ways of seeing, ways of knowing that are shaped by personal experience and through daily routines in time and place”

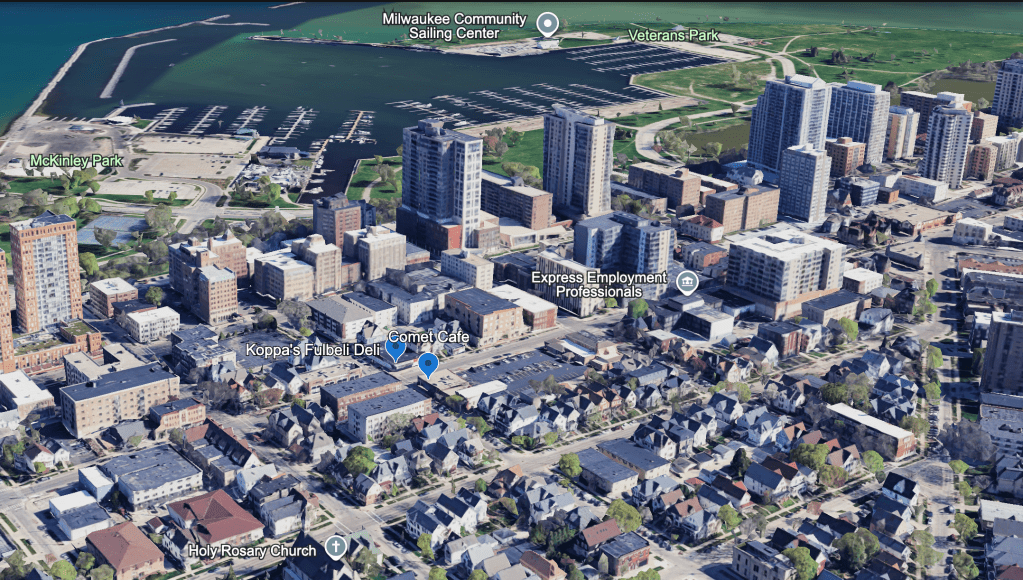

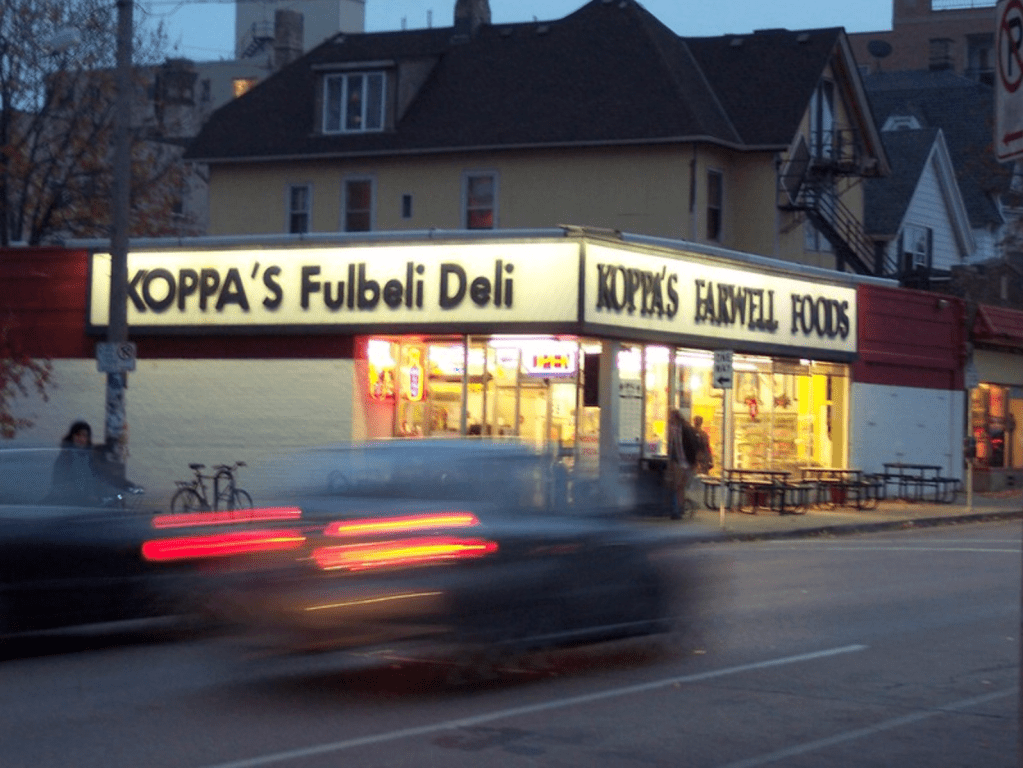

The buildings in focus are single-story commercial buildings on the southeast and southwest sides of the intersection. They are long-standing Lower East Side institutions, currently occupied by Koppa’s Fulbeli Deli and Comet Café. When examining internet communications about either establishment, you encounter the emotions synonymous with any such place that has existed for generations.

“For decades, Koppa’s Fulbeli Deli on the corner of Farwell and Irving has been a staple of the East Side community. Growing up, it was a landmark that let us know that we were almost to Brady Street. Synonymous with Milwaukee culture, Koppa’s was known for its deli sandwiches, kitschy decorations, and free Atari play.” -Sandy Reitman Shepard Express

“Unless it’s a small coffee house you can smoke in, it has not returned to its former glory. New Comet has and always will suck.”

-G0_pack_go reddit.com

To understand what shaped the intersection of Farwell and Irving, we must understand the East Side, the people who have and continue to shape it. Milwaukee is a city of neighborhoods, so I want to start with an overview of the East Side and then tighten the lens to focus on the intersection of Farwell and Irving.

What we find, through tracing this neighborhood and intersection through time, is the story of Milwaukee. The East Side’s growth flowed upriver from the 19th to the 20th century, following the boom of the industrial city; it showcases the evolution of transportation, and its public spaces demonstrate the virtues of the managerial Socialist government.

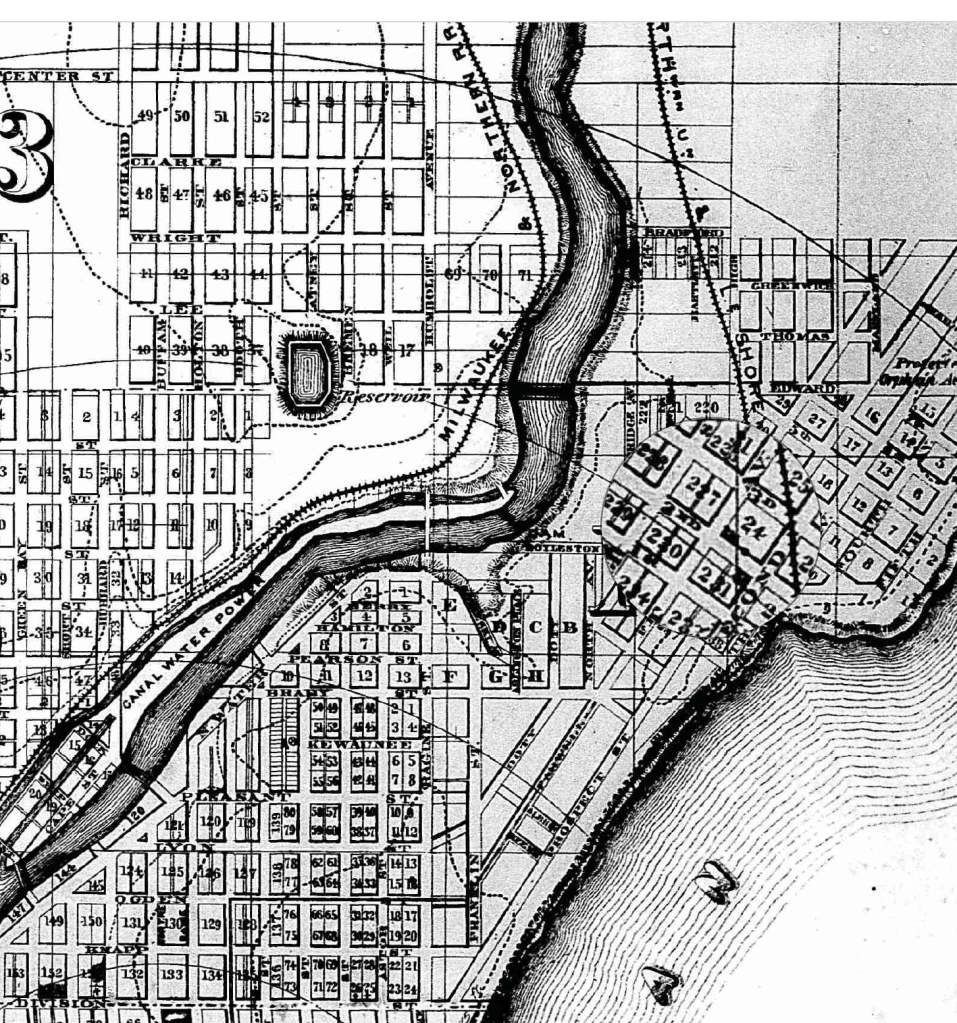

The Lower East Side, filled with folks who flowed north from Juneau Town, seeking a reprieve from the rapidly growing city. The growth of residents here was shaped by the physical geography and inherent economic prosperity of the water.

The East Side grew as industry grew, harnessing the power of the Milwaukee River not only with the North Avenue Dam to generate power, but also by connecting industry to the port and therefore the world. The Lower East Side would be filled with Polish immigrants, densely populated near their work on the river, while the bourgeoisie built large estates near the lake. This created a class dynamic that can still be seen in the geography of the neighborhood today. Some Victorian-style houses exist on the East Side; most of them have been replaced by high-rise apartments and condos, with most larger estates bordering Lake Park.

As the city grew, more groups moved into the East Side, and the Polish immigrants who helped to establish the neighborhood and Brady Street as the heart of commerce were joined by Italians. By the 1920s, the Italians would become the dominant force on Brady and occupy the minds of most Milwaukeeans today when they think of the ethnic roots of the area, as they were rooted there until the 1960s, when they began to disperse. These folks, and their religious faith, shaped the neighborhood and underscore the nature of change on the East Side.

Then, in the 1960s, a renaissance of counterculture and hippies moved into Brady Street, an area seen as a blighted area by city leadership, and in doing so, established the eccentric cultural beat that still drums in the Lower East Side today. While redevelopment during the following period of Milwaukee’s urban renewal reshaped downtown and spurred the growth of the high-density high rises that replaced most of the Victorian mansions that occupied Farwell and Prospect Ave, this resulted in an increase in the value placed on urban features that residents value today.

The early East Side was, as it is today, a mixed-class, ethnically diverse neighborhood, while the ethnic divides once held sharp lines; things today have softened. The neighborhood has evolved from being a place of families living intergenerationally near their work at the factories to being one, unique in Milwaukee, with larger proportions of both young adults and senior citizens than elsewhere in the city. In his chapter on the Lower East Side, John Gurda highlights this element, also emphasizing that 80% of housing is renter-occupied.

| LOWER EAST SIDE | MILWAUKEE |

| 3% under 16 years old | 24% under 16 years old |

| 20% 22-24 years old | 10% 22-24 years old |

| 14% >65 years old | ~9% >65 years old |

“From the mid- 1800s to the twenty-first century, from the phalanx of high-rises overlooking Lake Michigan to the cluster of cottages near the Milwaukee River, the neighborhood has always been a cosmopolitan collection of different worlds. No true Lower East Sider would have it any other way.” -John Gurda

As Farwell intersects Brady, the fate of the streets is linked with the development of transportation between them. At the time of their construction, the buildings that house Koppa’s, built in 1926, and Comet, built in 1924, the automobile had not emerged as the dominant form of transportation on the densely populated East Side.

This is evidenced morphologically in lots that lack driveways and density of lots; if there exists a place for a car today, it is typically a detached garage that is accessed from the alley. Bus stops for the 30 and Green Line, offering high-frequency service, are nearby. The regularity of bike racks, Bublr bike share hubs, and e-scooters demonstrates the varied mobility that this urban area encourages.

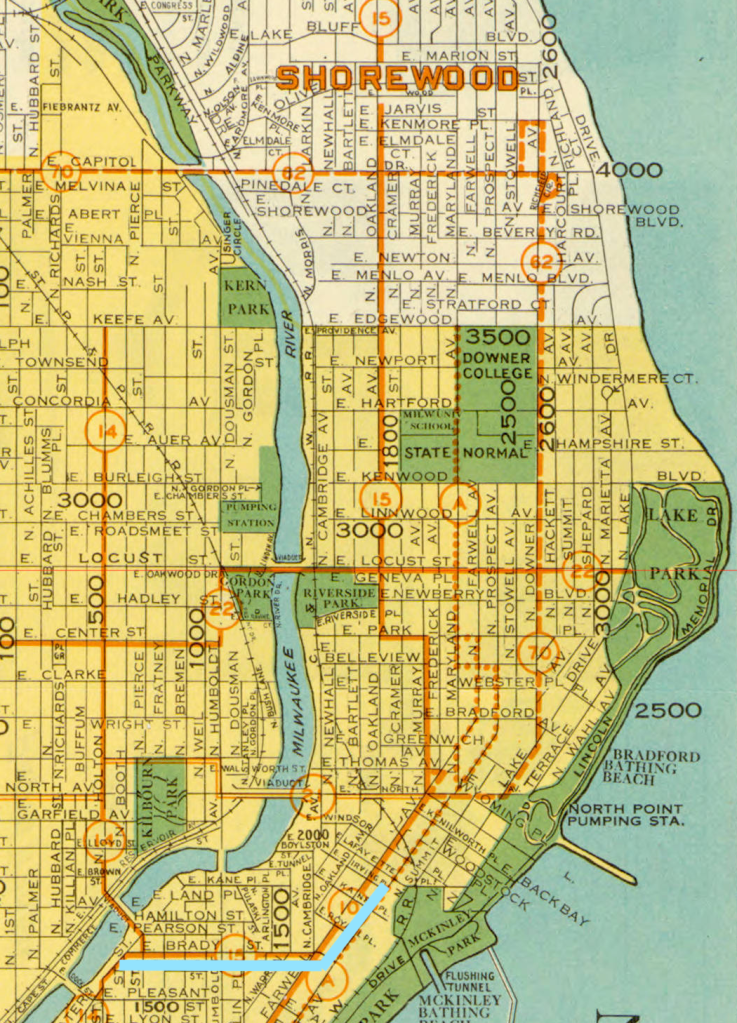

At the time the buildings I am examining emerged in the 1920s, the electric streetcar, Line 10, was the people mover of Farwell Ave.

It also connected, via the 15, to the commuter suburb of Shorewood, allowing access to the businesses that filled Farwell.

To the right first we see a map of the streetcar lines followed by aerial photos showing the evolution of the block.

When thinking about what shaped activity around Farwell and Irving. We can look to Milwaukee’s Socialist mayors is the construction of the Olmsted-designed Lake Park. With this, the early 20th century would set the precedent for the value of public parks and Milwaukee’s dedication to the parks movement.

Which is important when examining Farwell and Irving, as within a comfortable walk for most is the East Bank Trail, Milwaukee River Greenway, Bradford Beach, and Oak Leaf Trail. If the value of public green space and this connection to nature and recreation had not been emphasized, perhaps a bit of the neighborhood’s vitality would be lost, especially during the summer when numerous festivals take place on the nearby lakefront and the beer gardens open.

“Opportunity and inducement to escape at frequent intervals from the confined and vitiated air of the commercial quarter, and to supply the lungs with air screened and purified by trees, and recently acted upon by sunlight, together with opportunity and inducement to escape from conditions requiring vigilance, wariness, and activity to other men… ” – Fredrick Law Olmsted

The continued role of the city and other elements of urban governance can be considered in the later changes of the Lower East Side. Community groups played a role in halting the construction of the Park East Freeway and institutions, like UW-Milwaukee, influenced the redevelopment of the “stub end” of the freeway.

A 1981 study from the University of Milwaukee’s School of Architecture and Urban Planning explored the Lower East Side, defining what shaped the place, what the needs were at the time, and what should be preserved in response to proposals to redevelop the area occupied by said “stub end”.

From the report. A caution to hold in focus who the development would serve.

“If Milwaukee follows national patterns, there will be an increase in property values, speculation, housing prices, rents, and taxes. A certain amount of reinvestment is good for neighborhood growth and stability, but one must remember that a neighborhood is not only its buildings, but also its people. What makes the Lower East Side such an unusual community is its diversity, both in building types, and more importantly, people.”

Part of the area was developed into the East Pointe Commons. A demonstration of the New Urbanism movement, with both density and the beloved front porches of Mayor Norquist, to facilitate interactions and observance of the street.

Moving into the intersection of Farwell and Irving, we can track the way the built environment has evolved in the way these addresses have amalgamated to their current singular occupants.

Land Use change

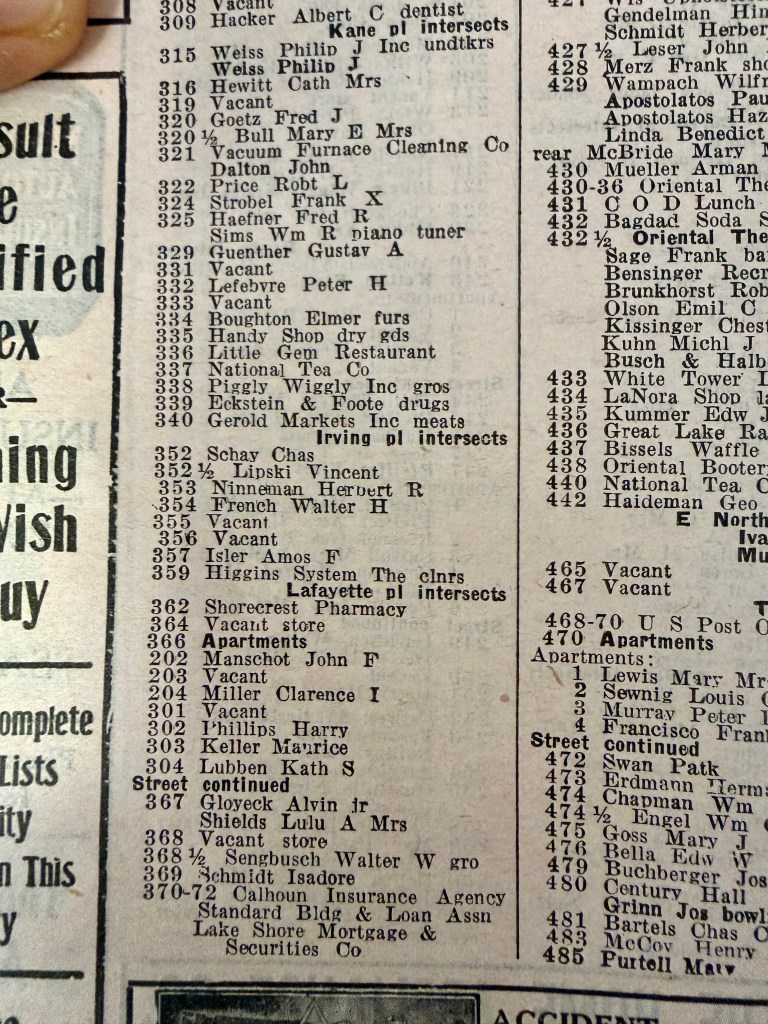

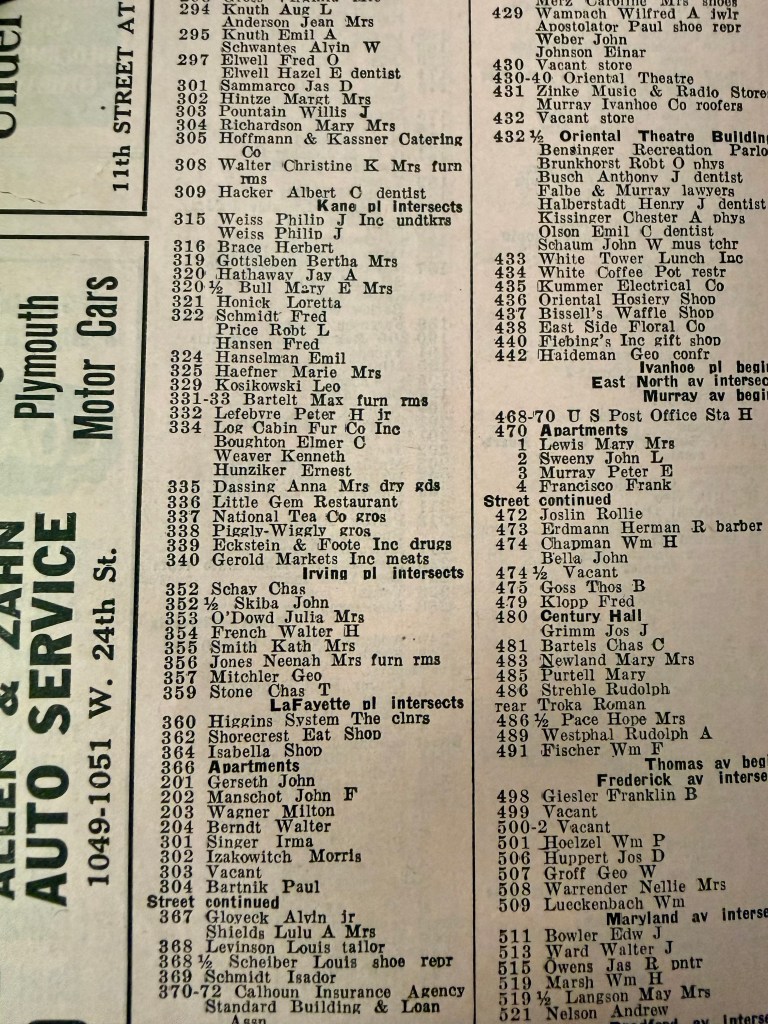

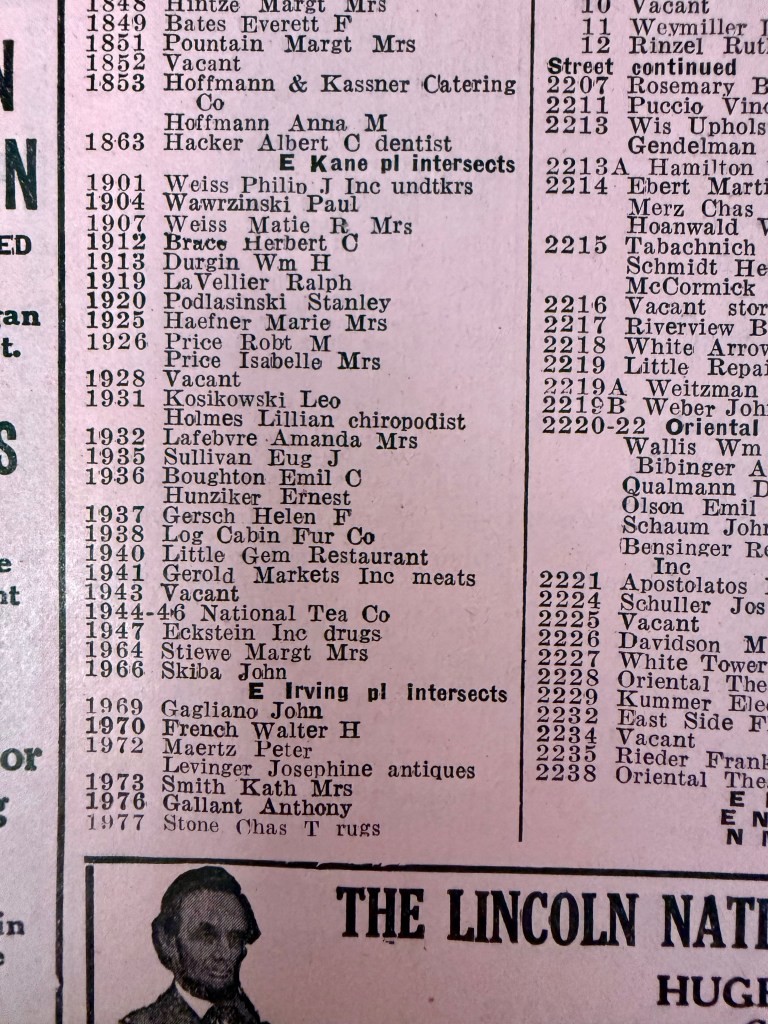

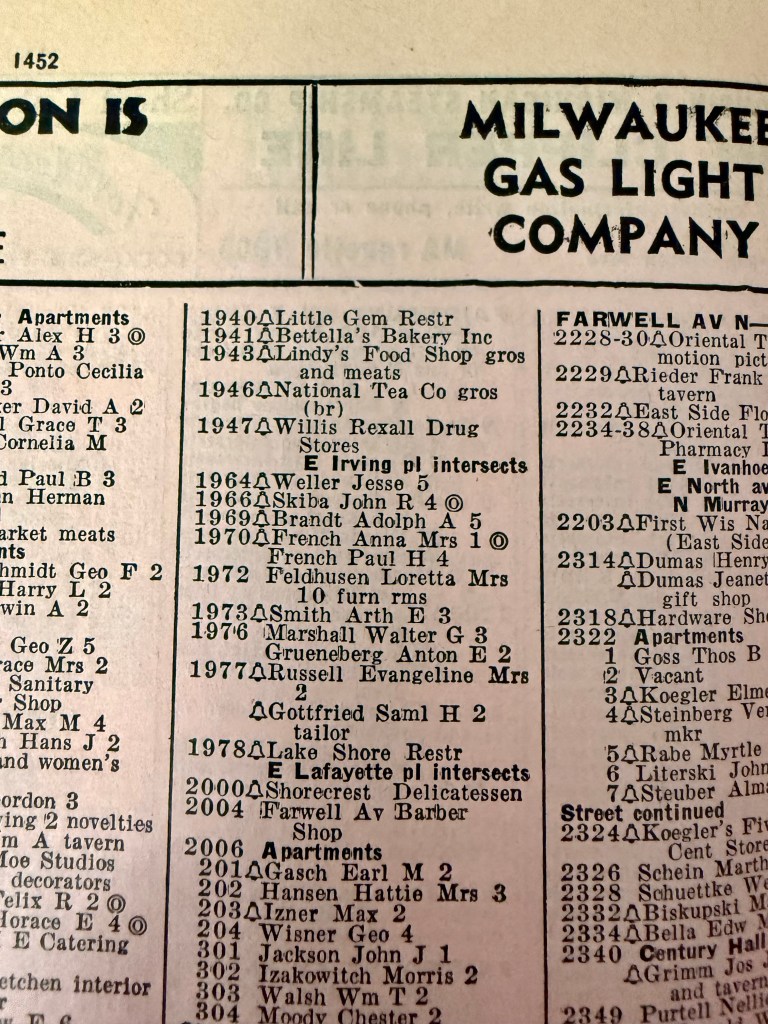

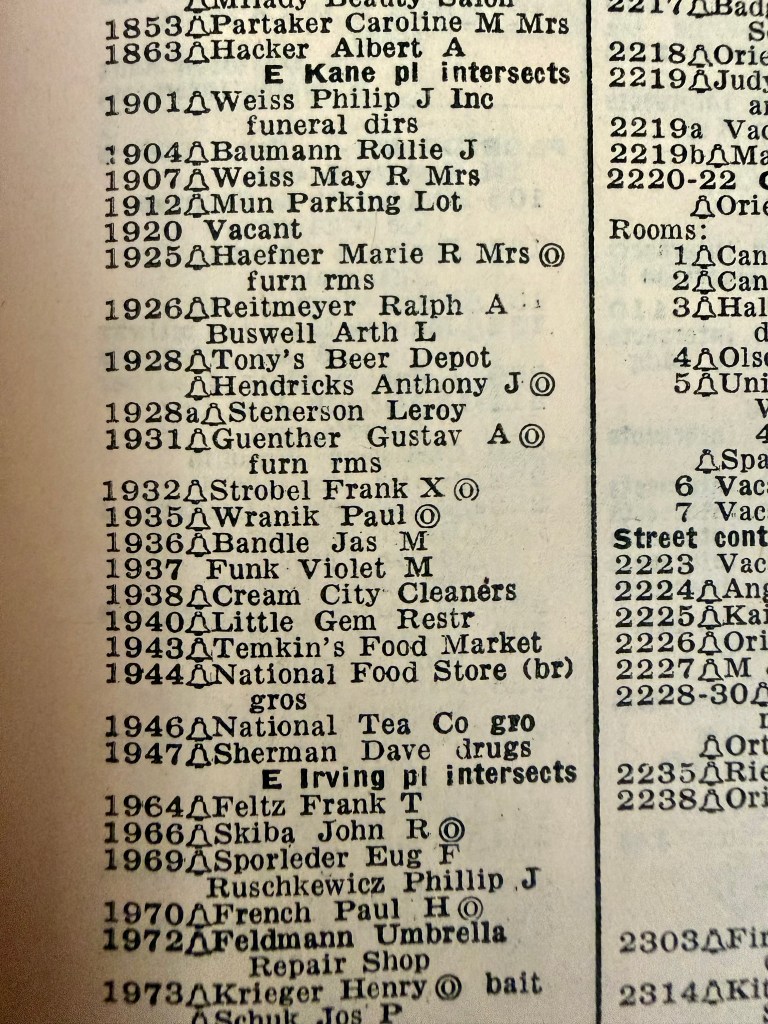

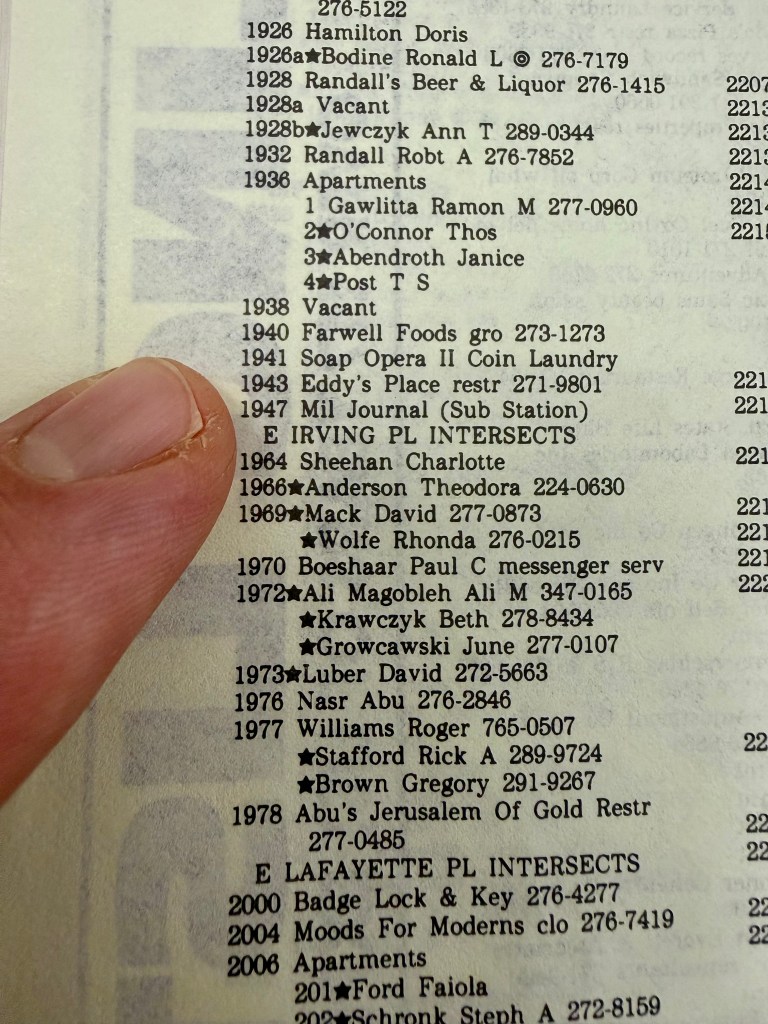

In Milwaukee City directories we follow the buildings’ evolution from multiple businesses to one.

1924 1941-1947 N Farwell Ave built

1928

National Tea Company

Eckstein & Foote Drugs

1933

Gerold Markets Meats

Eckstein Drugs

1941

Bettella’s Bakery

Lindy’s Food Shop

Willis Rexal Drugs

1955

Temkin’s Food Mart

Sherman Dave Drugs

1968

Megna TV and Appliance

Little Gem Restaurant

Lakewood Pharmacy

1987

Soap Opera II Coin Laundry

Eddy’s Place Restaurant

Milwaukee Journal Substation

1995

Comet Cafe

1926 1940-1946 N Farwell Ave built

1928

Little Gem Restaurant

Piggly Wiggly Inc Grocers

Gerold Markets Meats

1933

Little Gem Restaurant

National Tea Company Grocer

1941

Little Gem Restaurant

National Tea Company Grocer

1955

Little Gem Restaurant

National Food Store

1968

IGA Foodliner Grocery

1987

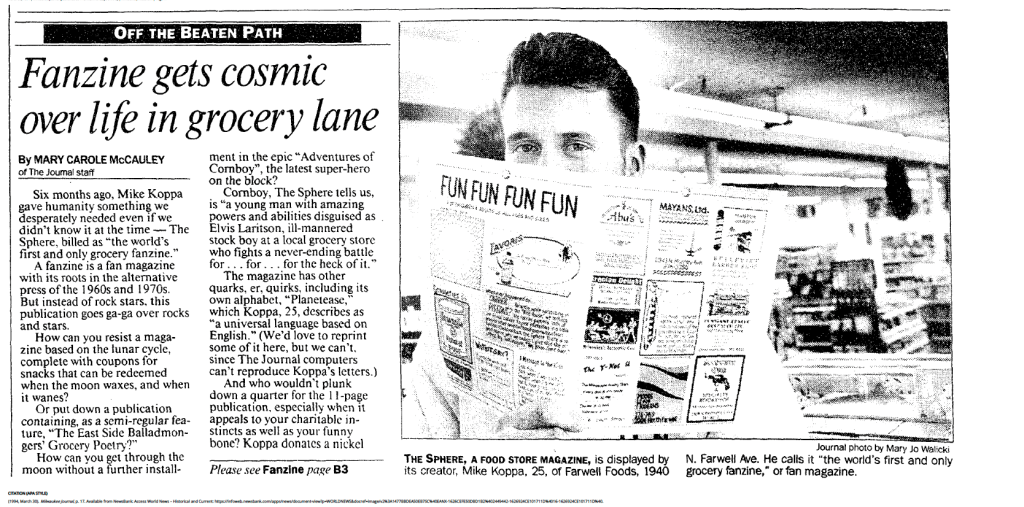

Koppa’s Farwell Foods

1995

Koppa’s Fulbeli Deli

Here are photos of the directories. We can see the change of street numbers and the disappearance of whole structures.

Both places serve as reflections of the culture and societal changes that have occurred in their 100-year tenure in the neighborhood they serve. The space that holds Comet displays a varied history as a drug store, appliance store, laundry mat, newspaper distribution, and grocery store.

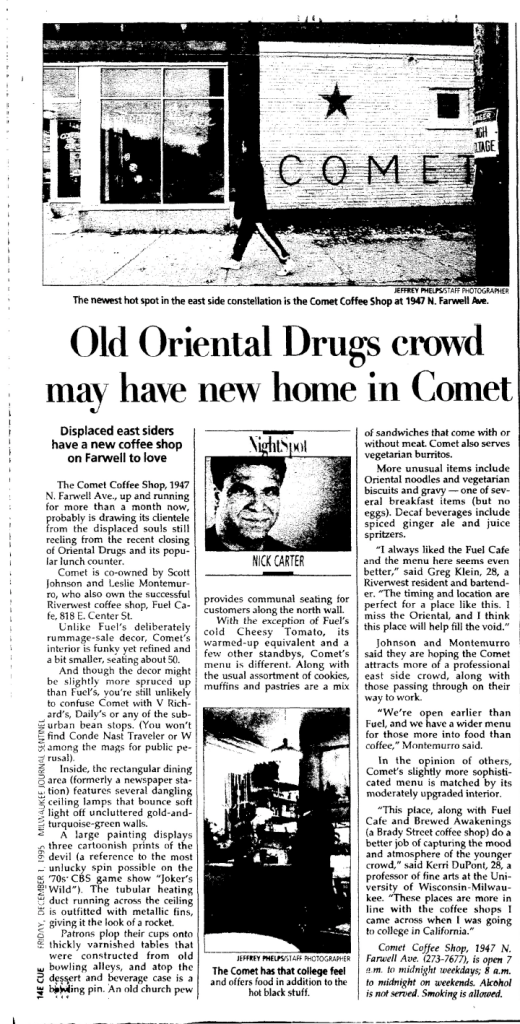

In a Milwaukee Journal article from 1995, when Comet started its takeover of the space, it was questioned if the new diner would take the place of a long-time East Side institution, Oriental Drugs, a pharmacy, diner, and general store that served as a third space in a time before the phrase was common vernacular.

I have included a documentary about Oriental Foods, as it is a further demonstration of the identity of the Lower East Side neighborhood that it served as well as elicits a commentary on larger societal changes. The parallel drawn to Comet is curious, as there have been various drug stores and restaurants that called the intersection of Farwell and Irving home for much of its early life; however, it leads to questioning what is lost when these gathering spaces are literally absorbed by their successors. Comet does not provide the same services as Oriental Drugs, nor did it replace in kind the former occupants of the building. Is the local cultural value of a place transferable?

At the time of Comet’s opening, there already existed a veneration of Koppa’s, and Comet would go on to become its own hallowed gathering space, holding the memories of moments and providing a comfortable familiarity. Both buildings have been shaped by the neighborhood they occupy and shape the residents as well.

What stands out is the significance of food in the history of these buildings. Food is a defining element of a culture; to be a place that feeds a neighborhood attaches itself to a basic unifying need. These buildings could serve any number of uses, but being a place that enroots itself in the definition of a neighborhood’s culture gives them longevity. Perhaps that is why these buildings on the corner of Farwell and Irving’s morphological change resulted in their amalgamation rather than destruction. In serving the community food, a place, such as Comet, acts as a vault holding memories and creates a 3rd space and enmeshes itself in a neighborhood.

Koppa’s and Comet, serve as reflections of East Side culture, to survive, they had to understand their customers and show flexibility to adapt as time moved on. It is inevitable is that these buildings will change, as we see they have in the past, but their significance to those who live nearby and their place in the neighborhood culture can last.

References:

G0_pack_go] (2024) Has Comet returned to its former glory? [Online forum post]. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/milwaukee/comments/1g0t1er/comment/lrbkbt5/

Reitman, S. (2025, August 15) Koppa’s fulbeli deli’s makeover. Shepard Express. https://shepherdexpress.com/food/eat-drink/koppas-fulbeli-delis-makeover/

Encyclopedia of Milwaukee (2016) East Side. In Encyclopedia of Milwaukee. Retrieved December 3, 2025, from https://emke.uwm.edu/entry/east-side/

Simon, R. D. (1976) The City-Building Process: Housing and Services in New Milwaukee Neighborhoods 1880-1910. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. p.45-53 https://archive.org/search.php?query=external-identifier%3A%22urn%3Aoclc%3Arecord%3A1148230972%22

Gurda, J. (2015). Milwaukee. City of neighborhoods. Historic Milwaukee Inc.

Olmstead, F. L. (1870). Public parks and the enlargement of towns. [Address] American Social Science Association meeting, Lowell Institute, Boston University, Boston, MA, United States.

Abbot, D., Friedman, D., Kerski, M., Papp, E. (1981). The Park East design study. University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

Sharma-Jensen, G. (1995, February 19). Straight-laced grocer gets funky. Milwaukee Journal. p. 59

McCauley, M. (1994, March 30). Fanzine gets cosmic over life in grocery lane. Milwaukee Journal. p. 17

Carter, N. (1995, December 1). Old Oriental Drugs crowd may have home in Comet. Milwaukee Journal. p.52

Maroldi, B. [brookeoverthere]. (2021, April 25) Death of a corner drugstore [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/nYE4gwKKLMw?si=giF9_XAYL22mJleX

Radio Milwaukee. (2016, May 4) Milwaukee with John Gurda: East Side episode 6 [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/fvovkFrTk_g?si=lyPjD8PZzkrRMXVt

(1928) Wright’s Milwaukee (Wisconsin) city directory (Pt. 2) Wright Directory Co.

(1933) Wright’s Milwaukee (Wisconsin) city directory (Pt. 2) Wright Directory Co.

(1941) Wright’s Milwaukee (Wisconsin) city directory (Pt. 2) Wright Directory Co.

(1955) Wright’s Milwaukee (Wisconsin) city directory (Pt. 2) Wright Directory Co.

(1968) Wright’s Milwaukee (Wisconsin) city directory (Pt. 2) Wright Directory Co.

(19987) Wright’s Milwaukee (Wisconsin) city directory (Pt. 2) Wright Directory Co.

Images:

(1885). Prospect Ave [Photograph]. University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries. https://collections.lib.uwm.edu/digital/collection/mkenh/id/290/rec/23

(1885). Prospect Avenue, Charles Ray House [Photograph]. University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries. https://collections.lib.uwm.edu/digital/collection/mkenh/id/288/rec/24

(1986). 1857B N Pulaski. [Photograph]. Wisconsin Historical Society. https://wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Property/HI105556

(unknown) Lake Park and drive. [Postcard]. Wisconsin Historical Society. https://wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM55052

Mayer, H. (1974). Milwaukee River Dam. [Photograph]. University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries. https://collections.lib.uwm.edu/digital/collection/mkenh/id/128/rec/32

Mayer, H. (1977). Frederick C. Bogk House, 2420 N Terrace Avenue. [Photograph]. University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. https://collections.lib.uwm.edu/digital/collection/mkenh/id/4/rec/45

Mayer, H.(1975). Brady Street, looking east from Humboldt Avenue [Photograph]. University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries. https://collections.lib.uwm.edu/digital/collection/mkenh/id/76/rec/16

Mayer, H. (1985). Bradford Beach, Lake Michigan. [Photograph]. https://collections.lib.uwm.edu/digital/collection/mkenh/id/31/rec/56

Mayer, H. (1991). East Pointe Commons apartments. [Photograph]. University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries. https://collections.lib.uwm.edu/digital/collection/mkenh/id/6/rec/3

Mayer, H. (1978). Pfister and Vogel Tanning Company building. [Photograph]. University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries. https://collections.lib.uwm.edu/digital/collection/mkenh/id/199/rec/10

US Dept. of Agriculture (1937) Milwaukee, County WI 22-2074. [Photograph]. Wisconsin State Cartographer’s Office. https://maps.sco.wisc.edu/whaifinder/?center=-87.8683%2C43.0526&level=14

US Dept. of Agriculture (1956) Milwaukee, County WI IR-42. [Photograph]. Wisconsin State Cartographer’s Office. https://maps.sco.wisc.edu/whaifinder/?center=-87.8683%2C43.0526&level=14

US Dept. of Agriculture (1963) Milwaukee, County WI 1DD-016. [Photograph]. Wisconsin State Cartographer’s Office. https://maps.sco.wisc.edu/whaifinder/?center=-87.8683%2C43.0526&level=14

US Bureau of Land Management (2000) Milwaukee, County WI Milwaukee SE 22-2074. [Photograph]. Wisconsin State Cartographer’s Office. https://maps.sco.wisc.edu/whaifinder/?center=-87.9069%2C43.0486&level=13

Google Earth Pro. Retrieved: December 8, 2025 https://earth.google.com/web/@43.05604322,-87.88934507,200.58511189a,1000.11852023d,30.00000004y,0h,0t,0r/data=CgRCAggBMikKJwolCiExekZMZ0ctUXRvNUp5eEszdW1fZ1Y5NnozNzVLSkVmWUIgAToDCgEwQgIIAEoICPLDlLQCEAE

Leave a comment